During my third year at University of Michigan, where I was studying biochemistry and French, I became aware of an unfamiliar, jarring sensation—extreme dizziness. If I closed my eyes for just a little bit, I’d feel my surroundings spinning. It was around the same time I recognized my difficulties hearing in large lecture halls.

Moving on From Ménière's

About eight years ago when I was 46, a few days after having a very stressful cataract surgery, I started to trip over my own feet. My balance has never been very good, but this was out of the ordinary, even for me. I had to ask my husband to come home from work to take care of our 8-year-old son. After the attack passed, I noticed that I wasn't hearing very well out of my right ear. I went to the doctor, who thought it was a sinus infection and gave me an antibiotic.

2020-2021 Emerging Research Grants Recipients Announced

Starting with this 2020–2021 ERG cycle, HHF is increasing the available annual amount per project to $50,000 and will also make grants renewable for a second year. We look forward to learning about the advances these promising researchers will undoubtedly make in the coming year and beyond.

Stability in an Unstable World

By studying the mouse brain, Balmer and Trussell have now mapped the direct and indirect circuits that carry sensory information to the vestibular cerebellum. Both types of input activate cells within the vestibular cerebellum called unipolar brush cells (UBCs).

Becoming a Champion

At this point I can say Ménière's disease and my initial negative experiences in undergraduate school have impacted my life for the better. Ménière's is a lonely condition but it’s forced me to become much more self-reliant.

How Ménière's Led Me to a Master’s

By Anthony M. Costello

Ménière's disease initially presented itself to me 20 years ago in a violent and unfortunate manner. I was 16 attending a New England boarding school when I experienced a vestibular (balance) episode, and it changed my health and life forever.

I remember vividly the vertigo that, without warning, controlled me. I remember the incredible pressure and fullness in my ears and the overwhelming sense of nausea. Realizing I could not stand I sought refuge in my bed, where the sensation of spinning intensified and I vomited profusely.

The school staff could only assume I was intoxicated and took disciplinary action. As I could not yet explain or understand that my behavior was caused by Ménière's disease, I had little recourse to justice. Faced by more unfair treatment, I left the school at the end of the academic year.

For the remainder of high school, I continued to struggle with bouts of vertigo, dizziness, and imbalance. These symptoms impacted my athletic performance, my ability to concentrate on my schoolwork, and my general quality of life. It was a difficult and confusing time as I appeared fine on the outside but I was internally battling a miserable existence that I could not fully understand or control. That paradox has since defined my life.

Shutterstock

When I received a formal diagnosis, my thoughts, priorities, and routines obsessively revolved around managing my wellness. This new mindset made it difficult to relate to the life I once had or to the lives of those around me. I made great efforts to hide my symptoms and protect loved ones from the negative emotional and physical effects of my disease. I made excuses to avoid social events just because of my illness.

Ménière's disease has repeatedly left me in states of hopeless despair. While it can be perceived as “strong” to persevere through one’s condition independently, I have learned this only leads to more isolation. Ménière's takes so much from its sufferers; it attacks their bodies, tests their spirits, and consumes their thoughts. This is why it is so important to reach out, be honest, and bring others into your world that you trust while you are living with Ménière's. Otherwise, you deprive yourself of not only your health but the relationships you deserve.

The etiology of Ménière's disease remains scientifically disputed and I do not claim to have the answer. But I do know the condition does not respond well to stress. I’ve spent every day of my life carefully crafting my decisions and actions based on how my Ménière's may react. In the process, I’ve come to master handling and mitigating stress. In fact, at 30 I went back to school for a master’s in psychotherapy in part to study stress and the human mind. I now licensed psychotherapist, a career change inspired by my conversations with newly diagnosed Ménière's patients in the waiting room of my ear, nose, and throat doctor’s office.

I have been fortunate to have had periods of relative remission with reduced vertigo. But there is a misconception that Ménière's just comes and goes, allowing the sufferer to return to normalcy in the interim. In reality, part of it is always there, be it the tinnitus, the difficulty hearing people in a crowded room, or the feeling the floor will start moving. There is always the uncertainty of what tomorrow will bring.

Using mindfulness—a meditation technique that helps one maintain in the present without judgment—has been helpful in calming my anxiety. Mindfulness is especially useful when my tinnitus feels overwhelming, and I sometimes I combine the practice with music, a white noise machine, or masking using a hearing aid.

I try to live my life in a manner in which Ménière's never wins. This disease will bring me to my knees—both literally and figuratively—but I just keep getting up. You can’t think your way out of this disease and spending all your time in a web of negative thoughts can be as toxic to your mind as Ménière's is to your inner ears. In my hopelessness, I try to stop my mind from plunging into the abyss and use every tool I can—making plans see friends and family, finding glimpses of joy in the midst of darkness, or being physically active. You have to retain some control when you feel like you have none.

The only gift that Ménière's has given me is a level of introspection and awareness that I could not have attained in 10 lifetimes. It has stripped me down to my core and forced me to explore what is truly important and made me a better person. I don’t know who I would be without this disease, but I’m positive that person could not fathom the joy or gratitude I find in a moment of health.

Anthony M. Costello, LMFT, lives in Byfield, Massachusetts with his wife, daughter, and 2 dogs. He has a private practice and specializes in helping others with chronic illness. For more, see www.costellopsychotherapy.com.

Receive updates on life-changing hearing and balance research, resources, and personal stories by subscribing to HHF's free quarterly magazine and e-newsletter.

Painting for a Cure

By Nicolle Cure

(Desplácese hacia abajo para ver la traducción al español.)

Credit: Lia Selfridge

My art is the fuel that ignites my passion for helping others. I use my art as a tool to create so that I can support the causes I believe in. Throughout my life, I have created several collections, for the most part biographical. To date, I've been blessed to have the opportunity to collaborate with animal welfare campaigns as well as education and health research initiatives. I am now proudly raising awareness about a particular cause that is dearest to my heart—hearing loss and vestibular (balance-related) disorders—after experiencing these conditions myself.

On August 4, 2017, I woke up and noticed that the right side of my head was numb. I felt a strong pressure in my right ear and couldn’t hear anything as my ear felt blocked and full. It was really scary and very sudden.

Since that day, I have been in and out the hospital trying to decipher what is wrong with me and how to cure it. My first audiology appointment showed a profound hearing loss in my right ear, and after steroids injected into the middle ear for two months, I was able to recover the ability to hear low frequencies. However, the high frequencies only improved to severe (from profound), which is why I now suffer from tinnitus and I am extremely sensitive to environmental sounds.

My hearing loss was only the beginning. During the initial months, I also suffered from BPPV (benign paroxysmal positional vertigo), debilitating vertigo episodes, chronic migraines, constant nausea, and dizziness. My balance was completely off and I swayed to the right when walking. It felt like I was walking on quicksand. Another symptom that persisted for months was chronic fatigue, to the point that I could not get out of bed on certain days. My body felt heavy as if I had a slab of concrete on top of me.

Nicolle painting in her studio. Credit: Lia Selfridge

These “invisible conditions” can really affect patients an emotional level. I was completely isolated from the world, I didn’t want to see anyone, and I avoided phone calls and going out. I’ve always been a very independent person and the fact that I couldn’t do anything or go anywhere made me feel frustrated most of the time.

My boyfriend Felipe, a communications professional and music producer, has been the greatest companion, helping me thrive and heal with his patience and love, and for that I am truly grateful. We share a passion for music and going to concerts, but from the time of my hearing loss I avoid loud places and crowds in general. I know music to him means as much as art to me, so I now wear custom musician’s earplugs. I am also investigating a hearing aid for my right ear, which my audiologist recommended after a recent tinnitus assessment to manage my tinnitus and sound sensitivity. Vestibular rehab therapy helped me regain my balance, as I had difficulty walking or even just standing still.

And of course my art has been my most powerful coping mechanism. While I am in the process of creating, I can focus better and forget about my symptoms. Painting makes me ignore my tinnitus even for a short period of time.

This experience has given me the opportunity to create awareness about invisible conditions. It is a fuel that continues to ignite my passion for the arts and for helping others. It has given me a sense of purpose—I truly feel the need to wake up and create something beautiful to deliver a powerful message of positivism in spite of my symptoms.

In “The Colors of Sound” painting collection, I am trying to capture emotions and moods in sound. Using his recording equipment, Felipe showed me the range of frequencies that I was not able to hear anymore. It was a bizarre experience to be able to see the sound waves and frequencies that I could no longer hear. These ink paintings replicate the energy and movement of what was now missing.

Behind every invisible illness there are wonderful individuals with the will to thrive and heal. Helping others has been incredibly therapeutic for me, and I gained so much support from people, too. I want to create a space for dialogue so people can be open about their conditions and find treatments and relief and know that they are not alone in this journey.

Nicolle Cure is an artist based in Miami. “The Colors of Sound” appeared at Art Basel in Miami Beach (December 2017–February 2018). Read an expanded version of this post and see more photos of her art in her Winter 2019 cover story of Hearing Health magazine.

Pintando para una Cura

Por Nicolle Cure

Crédito: Lia Selfridge

Mi arte es el combustible que enciende mi pasión por ayudar a los demás. Utilizo mi arte como una herramienta para crear y poder apoyar las causas en las que creo. A lo largo de mi vida he creado varias colecciones, en su mayoría biográficas. Hasta la fecha, he tenido la suerte de contar con la oportunidad de colaborar en campañas de bienestar animal, así como en iniciativas de investigación en educación y salud. Ahora estoy, orgullosamente, creando conciencia sobre una causa en particular que es lo más querido en mi corazón: la pérdida de audición y los trastornos vestibulares (relacionados con el equilibrio)-después de experimentar estas condiciones yo misma.

El 4 de agosto del 2017 me desperté y noté que el lado derecho de mi cabeza estaba entumecido. Sentí una fuerte presión en mi oído derecho y no podía escuchar nada debido a que mi oído lo sentía bloqueado y lleno. Fue realmente aterrador y muy repentino.

Desde ese día he estado entrando y saliendo del hospital tratando de descifrar qué anda mal en mí y cómo curarlo. Mi primera cita con el audiólogo mostró una pérdida auditiva profunda en mi oído derecho, y después de inyectarme esteroides en el oído medio durante dos meses, pude recuperar la capacidad de escuchar las frecuencias bajas. Sin embargo, las frecuencias altas solo mejoraron al nivel de severo (de haber estado en el nivel profundo), y es por eso que ahora sufro de tinnitus y soy extremadamente sensible a los sonidos ambientales.

Mi pérdida de audición fue solo el comienzo. Durante los primeros meses también sufrí de VPPB (vértigo posicional paroxístico benigno), episodios de vértigo debilitantes, migrañas crónicas, náuseas constantes y mareos. Mi equilibrio estaba completamente perdido y me balanceaba hacia la derecha al caminar. Me sentía como si estuviera caminando sobre arenas movedizas. Otro síntoma que persistió durante meses fue la fatiga crónica, hasta el punto de que no podía levantarme de la cama ciertos días. Mi cuerpo lo sentía pesado, como si tuviera una losa de concreto encima mío.

Nicolle pintando en su estudio. Crédito: Lia Selfridge

Estas "condiciones invisibles" pueden afectar realmente a los pacientes a nivel emocional. Estaba completamente aislada del mundo, no quería ver a nadie y evitaba las llamadas telefónicas y salir fuera. Siempre he sido una persona muy independiente y el hecho de no poder hacer nada ni ir a ningún lado me hacía sentir frustrada la mayor parte del tiempo.

Mi novio Felipe, un profesional de las comunicaciones y productor musical, ha sido el mejor compañero, ayudándome a prosperar y sanar con su paciencia y amor, y por eso estoy realmente agradecida. Compartimos la pasión por la música y por ir a conciertos, pero desde el momento de mi pérdida auditiva evito los lugares ruidosos y las multitudes en general. Sé que la música para él significa tanto como el arte para mí, así que ahora uso tapones de oídos para músico, personalizados. También estoy investigando sobre un audífono para mi oído derecho, que mi audiólogo me recomendó después de una evaluación reciente del tinnitus, con el fin de controlar eso y mi sensibilidad al sonido. La terapia de rehabilitación vestibular me ayudó a recuperar el equilibrio, pues tenía dificultades para caminar o incluso para quedarme quieta.

Y por supuesto, mi arte ha sido mi más poderoso mecanismo de afrontamiento. Mientras estoy en el proceso de crear, puedo concentrarme mejor y olvidarme de mis síntomas. Pintar me hace ignorar mi tinnitus, incluso por un corto período de tiempo.

Esta experiencia me ha dado la oportunidad de crear conciencia sobre las condiciones invisibles. Es un combustible que sigue encendiendo mi pasión por las artes y por ayudar a los demás. Me ha dado un sentido de propósito: realmente siento la necesidad de despertar y crear algo bonito para transmitir un poderoso mensaje de positivismo, a pesar de mis síntomas.

En la colección de pinturas "The Colors of Sound” (“Los Colores del Sonido"), estoy tratando de capturar emociones y estados de ánimo en el sonido. Usando su equipo de grabación, Felipe me mostró el rango de frecuencias que yo ya no podía escuchar. Fue una experiencia extraña poder ver las ondas sonoras y las frecuencias que ya no escuchaba. Estas pinturas en tinta, replican la energía y el movimiento de lo que ahora estaba faltando.

Detrás de cada enfermedad invisible hay individuos maravillosos con la voluntad de prosperar y sanar. Ayudar a los demás ha sido increíblemente terapéutico para mí, y también obtuve mucho apoyo de la gente. Quiero crear un espacio de diálogo para que las personas puedan hablar abiertamente sobre sus condiciones, encontrar tratamientos y alivio, y saber que no están solas en este viaje.

Nicolle Cure es una artista radicada en Miami. "The Colors of Sound" apareció en Art Basel en Miami Beach (diciembre del 2017-febrero del 2018). Lea una versión ampliada de este artículo y vea más fotos de su arte, en la historia que corresponde a la portada de la revista Hearing Health de Invierno del 2019.

Traducción al español realizada por Julio Flores-Alberca, enero 2025. Sepa más aquí.

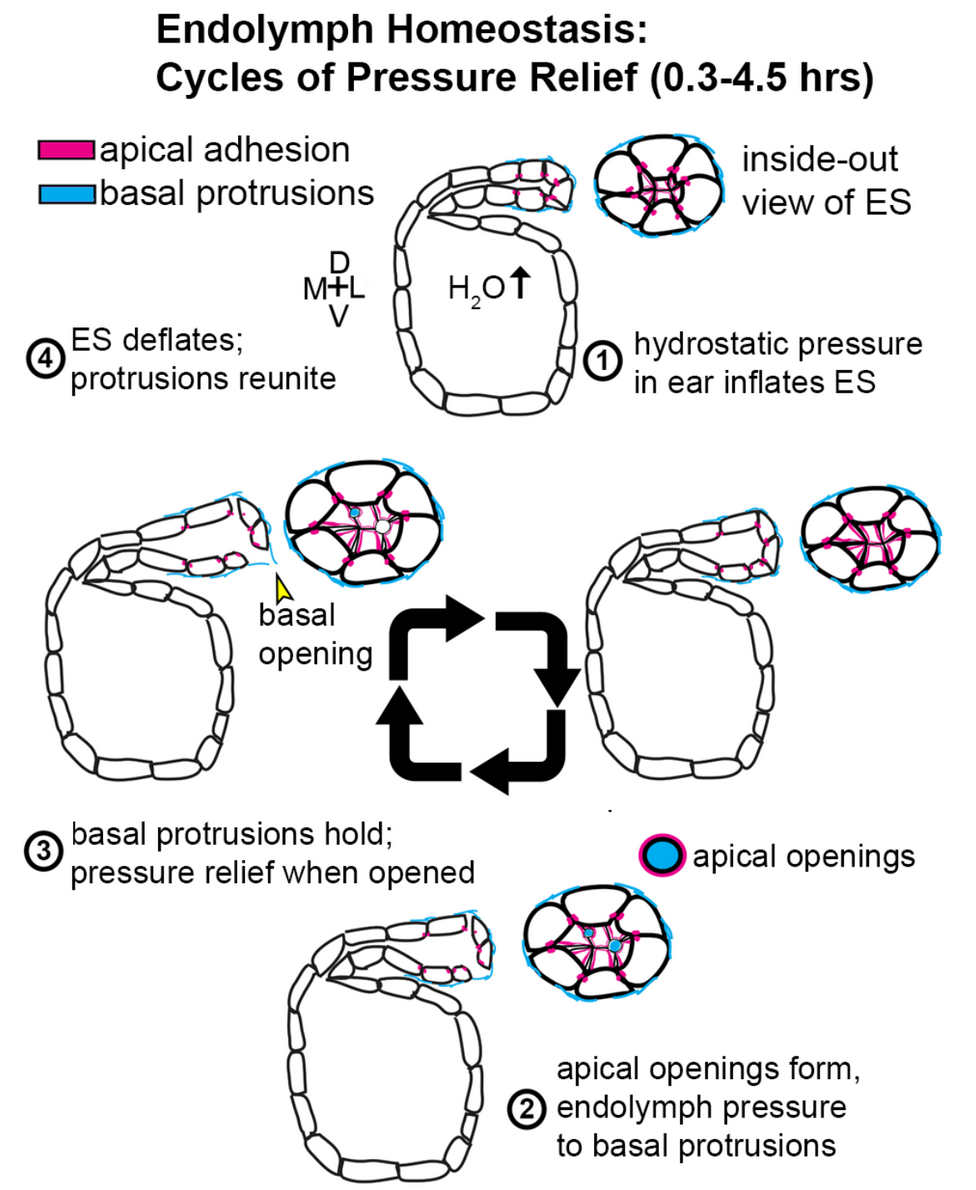

Understanding a Pressure Relief Valve in the Inner Ear

By Ian Swinburne, Ph.D.

The inner ear senses sound to order to hear as well as sensing head movements in order to balance. Sounds or body movements create waves in the fluid within the ear. Specialized cells called hair cells, because of their thin hairlike projections, are submerged within this fluid. Hair cells bend in response to these waves, with channels that open in response to the bending. The makeup of the ear’s internal fluid is critical because as it flows through these channels its contents encode the information that becomes a biochemical and then a neural signal. The endolymphatic sac of the inner ear is thought to have important roles in stabilizing this fluid that is necessary for sensing sound and balance.

This study helps unravel how a valve in the inner ear's endolymphatic sac acts to relieve fluid pressure, one key to understanding disorders affected by pressure abnormalities such as Ménière’s disease.

While imaging transparent zebrafish, my team and I found a pressure-sensitive relief valve in the endolymphatic sac that periodically opens to release excess fluid, thus preventing the tearing of tissue. In our paper published in the journal eLife June 19, 2018, we describe how the relief valve is composed of physical barriers that open in response to pressure. The barriers consist of cells adhering to one another and thin overlapping cell projections that are continuously remodeling and periodically separating in response to pressure.

The unexpected discovery of a physical relief valve in the ear emphasizes the need for further study into how organs control fluid pressure, volume, flow, and ion homeostasis (balance of ions) in development and disease. It suggests a new mechanism underlying several hearing and balance disorders characterized by pressure abnormalities, including Ménière’s disease.

Here is a time-lapse video of the endolymphatic sac, with the sac labeled “pressure relief valve” at 0:40.

2017 Ménière’s Disease Grants scientist Ian A. Swinburne, Ph.D., is conducting research at Harvard Medical School. He was also a 2013 Emerging Research Grants recipient.

Ménière's Disease Grantee Featured in Reader's Digest

Credit: Agnieszka Marcinska, Shutterstock

Ian Swinburne, Ph.D., a 2018 Ménière's Disease Grant (MDG) recipient, shared his expertise regarding vertigo with Reader's Digest in an article called "What Causes Vertigo? 15 Things Neurologists Wish You Knew" published in March 2018.

"The spinning, dizzying loss of balance which earmarks vertigo can come without warning," the article opens. Various professionals provide information about its duration, how it feels, and different types.

HHF-funded Dr. Swinburne notes specifically that the inner ear and balance disorder Ménière's disease can cause vertigo. He explains that "[b]outs of vertigo likely arise in patients with Ménière's disease, because the inner ear's tissue tears from too much fluid pressure—causing the ear's internal environment to become abnormal.'" He is currently pursuing a research project to understand the inner ear stabilizes fluid composition, which he believes will help to identify ways to restore or elevate this function to mitigate or cure Ménière's disease.

View the full article from Reader's Digest, here.

New Grantees Will Advance Understanding of Ménière's Disease

By Lauren McGrath

Hearing Health Foundation's (HHF) newly established Ménière's Disease Grants (MDG) program will significantly advance our understanding of the mechanisms of Ménière's Disease. In 2018, two innovators will have the opportunity to investigate the disorder's diagnosis and treatment.

Ménière's Disease is a disorder of the inner ear that causes episodes of vertigo as a result of fluid that fills the tubes of the inner ear. In addition to dizziness and nausea, Ménière's attacks can cause some loss of hearing in one or both ears and a constant ringing sound. The causes of Ménière's remain unknown and a cure has yet to be identified. The National Institutes of Health estimates that 615,000 individuals in the United States live with the disorder.

Two grants have recently been awarded for 2018 for innovative Ménière's Disease research. Both grantees were also previously funded by HHF’s Emerging Research Grants (ERG) program.

Gail Ishiyama, M.D.

Gail Ishiyama, M.D. of UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine is focusing on cellular and molecular biology of the microvasculature in the macula utricle of patients diagnosed with Ménière’s disease. Her project will provide greater information on the blood labyrinthine barrier and allow for the development of interventions that prevent the progression of hearing loss and stop the disabling vertigo in Ménière’s disease patients.

Ian Swinburne, Ph.D.

Ian Swinburne, Ph.D. of Harvard Medical School is classifying the endolymphatic duct and sac's cell types and their gene sets using high-throughput single-cell transcriptomics. His work will generate a list of endolymphatic sac cell types and the genes governing their function, which will aid in Ménière's diagnosis (which can be delayed due to the range of fluctuating symptoms) and the development of a targeted drug or gene therapy.

HHF is grateful for the opportunity to fund Drs. Ishiyama and Swinburne. If you are interested in naming a research grant in any discipline within the hearing and balance space, please contact development@hhf.org.