By Janice Schacter

Misconceptions about people with hearing loss are commonplace – some are antiquated stereotypes, while others just incorrect assumptions. It’s easy enough to get the wrong idea, as hearing loss can be an invisible disability – unlike the wheelchair that signals a mobility challenge. Whether it’s a total stranger trying to make small talk in sign language or an over-articulating coworker or relative, it’s time we initiated the conversation that will correct misconceptions and remove the stigma associated with deafness and hearing loss. This list of the more common misconceptions – and there are many more – can be a good starting point for that conversation.

1. EVERYONE WITH HEARING LOSS USES SIGN LANGUAGE AND READS LIPS.

Hearing loss spans across a spectrum from mild to completely deaf and not all people with hearing loss communicate the same way. Communication depends on a variety of factors, such as the degree of hearing loss, whether a hearing aid or cochlear implant is used, the age at which the person lost his hearing, the level of auditory training received, and the nature of the listening situation. The majority of people with hearing loss do not use sign language but it is still important to those whose communication depends on it.

American Sign Language is a visual language with its own syntax and grammar that is quite different from spoken and written English. Sign language varies by country as well. A person with some knowledge of sign language is not a substitute for a qualified interpreter who is trained to transmit what is said clearly and accurately.

Some people with hearing loss read lips and others do not. Lip reading, also called speech reading, is most helpful as a supplement to residual hearing, even though many speech sounds are not visible on the lips. It does help to face the person with hearing loss when speaking. Many people can pick up visual clues even if they are not proficient at lipreading.

2. TALKING LOUDER WILL HELP A PERSON WITH HEARING LOSS TO UNDERSTAND.

Increasing the volume is only part of the solution; clarity is also important. And there is a point where increasing the volume begins to distort the quality of sound. To obtain sufficient clarity, people with residual hearing may require sound to be transmitted from a microphone directly to their ear via an assistive listening system.

Sitting close to the speaker can assist the listener (it facilitates lip reading) but is not a substitute for an assistive listening system. Yelling and over-articulating does not help because these distort the natural rhythm of speech and make lip reading more difficult. A person who can hear normally cannot determine whether the sound is adequate for a person with hearing loss.

3. HEARING AIDS AND COCHLEAR IMPLANTS RESTORE HEARING TO NORMAL.

While highly beneficial in their impact, hearing aids and cochlear implants cannot restore hearing to “normal.”

A person does not obtain “normal” hearing by wearing a hearing aid or cochlear implant. These are not solutions for hearing that are equivalent to wearing glasses to correct poor eyesight. Hearing aids increase the volume but only slightly enhance clarity by raising the volume in certain frequencies. The improvement a cochlear implant makes can vary from providing near-normal hearing to only gaining an awareness of environmental sounds with no comprehension of what they mean. Results depend on such factors as the individual’s hearing history, length and onset of deafness, and age of implantation.

People with hearing loss may be able to understand and respond correctly many times by listening intently but they can miss important information. Furthermore, it can be tiring to listen intently for a prolonged period.

4. PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS ARE STUPID, MUTE, AND UNSUCCESSFUL.

People with hearing loss have the same range of intelligence as the general hearing population. People with untreated, or inadequately treated, hearing loss may respond in- appropriately since they may not have heard what was said.

Some people with hearing loss can speak and others cannot; again, there are many factors at play. A person who speaks well doesn’t necessarily hear well. And it can be frustrating or upsetting when others remark on how well they speak – and even more so if the remark is directed to a bystander, rather than directly to the person with hearing loss.

People with hearing loss are fully employable but may need certain accommodations for effective communication, as required by the Americans with Disabilities Act. It is always best to ask the person what type of accommodation is needed.

When conversing via telephone and using a relay service, there may be delays for interpreting or transcribing. People who are not familiar with relay services may wrongly assume that the lag time reflects on the level of intelligence of the person with hearing loss.

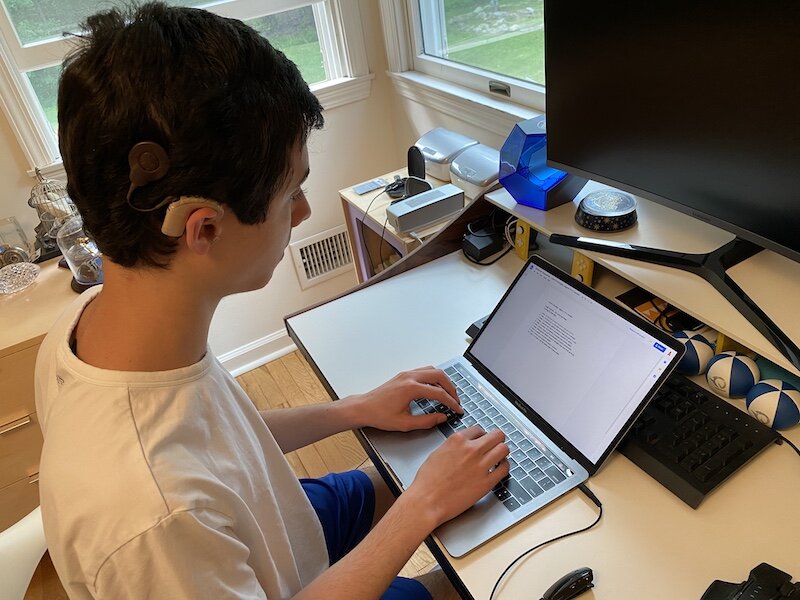

Hearing loss affects people of all ages. In fact, many people are born with a hearing loss, like Alex, 15, pictured above.

5. PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS TEND TO BE OLDER ADULTS.

Of the 48 million people with some form of hearing loss in the U.S. only one-third are 65 or older.

6. PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS ARE DEFINED BY THEIR HEARING LOSS.

Hearing loss is a characteristic, like the color of one’s eyes. It does not define a person. The “person” should be listed first, for example, “a person who is hard of hearing,” “a person who is deaf,” or “a person with hearing loss.”

7. HAVING HEARING LOSS IS SHAMEFUL.

This assumption at least partly explains why many people with hearing loss will not purchase or use hearing aids. According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, “Only one out of five people who could benefit from a hear- ing aid actually wears one.”

8. WHEN PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS MISS SOMETHING, IT’S OK TO TELL THEM, “IT’S NOT IMPORTANT,” OR, “I’LL TELL YOU LATER.”

It’s frustrating to people with hearing loss not to have something repeated when they miss part of the conversation. Saying, “It wasn’t important” compounds the frustration because now not only did they miss part of the conversation but the conversation is also being edited. The person with hearing loss wants to decide for himself or herself what is important.

9. PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS ARE RUDE AND PUSHY.

If a person with hearing loss interrupts a conversation, it is probably because they didn’t hear the speaker, not because they are rude. People with hearing loss may position themselves toward the front of a group or in a room so that they are closer to the speaker, making it easier for them to hear and lip read. This behavior is sometimes incorrectly interpreted as pushiness.

10. PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS MOSTLY HANG OUT WITH OTHER PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS.

Hearing loss can affect anyone and does not discriminate. People with hearing loss spend time with family or friends who may or may not have hearing loss. They do not want to be relegated to special seats away from the rest of the people they are with.

11. EVERYONE WHO NEEDS AN ASSISTIVE LISTENING SYSTEM CAN USE EARBUDS OR HEADPHONES.

Earbuds and earbud-style headsets require people with hearing aids to remove their hearing aids. Headsets typically do not work for people who wear behind-the-ear hearing aids nor for many people who have more than mild hearing loss because the sound output is insufficient.

People who have cochlear implants or T-coils in their hearing aids can receive signals directly through their hearing aid or cochlear implant when an induction loop is used. They can also ac- cess FM or infrared signals directly to their hearing aid or sound processor by using a neck loop receiver or an attachment (boot) to their aid or sound processor. The neck loop can be plugged into headphones but most one-piece headphones lack jacks.

12. THE WHEELCHAIR SYMBOL REPRESENTS UNIVERSAL ACCESS.

The wheelchair symbol does not represent people who are deaf, hard of hearing, visually impaired, or who have cognitive disabilities. Using the wheelchair as a symbol of universal access makes it more difficult for appropriate access to be obtained for other disabilities, since mobility is the only disability portrayed by this symbol.

It is also important to use the appropriate hearing loss symbols to specify the kinds of access being provided. There are different symbols for interpreting, assistive listening devices and systems, and open and closed captioning.

Many companies provide access information under the heading of “Access” or “Accessibility,” which is preferred to terms such as “Disabled Services” or “Handicapped Services,” since the latter imply a deficiency in the person rather than removal of barriers. However, as access is not limited to mobility impairments, business websites, brochures, and promotional materials should provide information for people with hearing loss, visual impairments, and cognitive disabilities as well.

Closed captions, shown above in this Hearing Health Hour webinar screenshot, are an example of access for people with hearing loss who benefit from visual cues when listening to a presentation.

13. HEARING ACCESS ISN’T NEEDED BECAUSE IT’S SO RARELY REQUESTED.

Many people with hearing loss are so accustomed to there being no accessibility accommodations that they don’t inquire about it unless it is publicized. Access, when made available and publicized, is usually used.

14. PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS READ BRAILLE.

People who are blind read Braille.

15. PROVIDING ACCESS FOR PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS IS VERY EXPENSIVE.

Hearing access is less expensive than most people think. Many solutions exist for just a few hundred dollars. Obtaining price estimates is advisable.

16. “DEAF,” “HEARING IMPAIRED,” “HANDICAPPED” OR “DISABLED” – ONE IS AS GOOD AS THE OTHER.

The umbrella term for the category is “people who are deaf or hard of hearing.” “Deaf” denotes a profound loss of hearing and can also be used to refer to the community of people who are deaf and share a language, such as American Sign Language, and a culture. “Hearing impaired” is not a preferred term.

17. COMPANIES OR ACCESSIBILITY EXPERTS WITH NO BACKGROUND WITH HEARING LOSS CAN KNOW WHAT BEST MEETS THE NEEDS OF PEOPLE WITH HEARING LOSS.

When hiring an access coordinator, it is critical to investigate the person’s experience. A person can be an expert in one area of access, such as mobility impairments, but may not understand access issues for people with hearing loss, visual impairments or cognitive disabilities. Also, hiring a person with hearing loss does not guarantee that the person has knowledge of effective access for people with hearing loss or for the full range of hearing loss.

Janice Schacter is a hearing loss advocate and founder of Hearing Access & Innovations. This article was developed in consultation with people and organizations representing people with hearing loss and originally appeared in Hearing Health magazine. This version has been updated for statistical accuracy.

Before I discovered CART, I often felt left out, despite being physically present. This gap in awareness affects thousands of people. That’s why I speak up, because access delayed is opportunity denied.