By Yishane Lee

Listen up, hearing is having a moment! Hear me out. We’re making some noise about safe listening.

And every other hearing pun you can think of, ahead of this International Noise Awareness Day, every year on the last Wednesday of April. The awareness day was conceived in the 1990s by HHF friend the Center for Hearing and Communication, based in New York City and Florida.

We have been heartened by the increased mainstream media coverage of healthy hearing lately—especially the emphasis on safe listening habits such as turning it down, carrying and using earplugs, knowing the decibel level and our daily sound dose, explanations of the logarithmic decibel (dB) scale, and ongoing efforts to regulate public noise levels.

These are all messages we’ve been promoting through our Keep Listening prevention campaign as part of our effort to create a culture shift around taking care of our ears. So, yay!

Here’s a look at what we’ve seen lately in the press. (Some may require creating an account or subscriptions.)

Scientific American: Former NPR health correspondent Joanne Silberner provides a comprehensive examination of noise and its effects on health, using the origin story of Quiet Communities Inc. (QC) as a framework. As friends of HHF may already know, Jamie Banks, Ph.D., started the organization as a way to combat the noise from gas-powered landscaping equipment.

The story traces the history of noise ordinances starting from the time of Julius Caesar up to a nearly forgotten 1972 Noise Control Act from the Environmental Protection Agency to limit sounds to an average 55 dB max over a 24 hour period—and how QC, which has expanded its advocacy for quieter hospitals, streets, and skies (and counting), and is an HHF partner—sued the EPA in June 2023 because this regulation is rarely enforced.

Silberner cites psychoacoustic expert Karl Kryter’s 1970 book, “The Effects of Noise on Man,” that helped inform the 55 dB limit. We tip our hat to HHF friend Daniel Fink, M.D., who first alerted us to Kryter’s work and the 1972 EPA Noise Control Act. (In fact these underpin Dan’s latest paper in Nature’s Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, “What is the safe noise exposure level to prevent noise-induced hearing loss?” Answer: an average 55 dB over 24 hours.)

We very much appreciate that this SA story helps us continue to work to overturn the notion that an 85 dB limit for the workplace is safe for the public at large. It is not. That 85 dB limit is for an eight-hour workday five days a week and does not take into account all the other noise we’re exposed to 24/7. This is especially egregious when 85 dB is cited as the so-called safe limit for kids’ headphones.

We also like the SA article* because it talks about the biology and evolutionary features behind hearing. Hearing’s “watchman function”—to be alert all the time, even when sleeping—to potential dangers was useful in primitive times but now has a negative effect not only on hearing but also overall health. Hearing is a sense you cannot turn off because it’s important for safety, and that’s all the more reason we need to make sure it’s protected, for life.

Washington Post: An opinion piece by Steve Wexler is titled, “Is a love of live music wrecking your hearing? Don’t let it.” A data visualization expert, Wexler uses graphics to show the reader how the logarithmic scale works, “where an 8.2 magnitude earthquake is 100 times bigger than a 6.2 earthquake,” and “going from 85 dB to 100 dB is a 3,100 percent jump” in sound intensity.

This is also something we’ve been trying to get across in our Keep Listening campaign. When Wexler translates the decibels into micropascals, a sound measurement that uses a linear scale, the difference between 85 dB and 100 dB is more apparent. In micropascals, it jumps from 356,000 micropascals to 2,000,000 micropascals. That’s much more understandable!

If you haven’t already tried this, I invite you to get out your favorite decibel reading app and turn up Alexa or Spotify or whatever is your preferred platform till it reads 85 dB. Just for a minute or two. It’s loud, right?

As Wexler points out, “It’s not just the volume level itself that can lead to permanent hearing loss, however. Other factors include the exposure on a given day, the cumulative exposure over years, and the frequency (pitch) of the noise.” We appreciate the reminders about daily sound doses and the cumulative exposure, like that to the sun or smoke.

Besides encouraging readers to think about earplugs “as sunscreen for your ears,” as ”any plug is better than no plug,” we love Wexler’s additional suggestion for music venues to not only have foam earplugs freely available for patrons but also display the decibel level so we can make informed decisions about our hearing. Showing the noise levels would be akin, he says, to a nutrition label on foods.

Or we could ask them to turn it down, even a little. Every 3 dB decrease in the 80s to 90s dB range would cut the risk to our hearing by half.

NPR podcast Life Kit: Reporter Margaret Cirino shares how her hearing was muffled for the entire next day after a concert, where she unfortunately stood near the speakers and had forgotten her earplugs.

She thought she’d permanently damaged her hearing, and that sent her investigating how to protect our ears. She speaks with the Hearing Loss Association of America’s Barbara Kelley, who gives a primer on hearing tests, hearing aids, and the risk to hearing from excess noise.

She also meets with an audiologist, Ariella Naim, Au.D., to test her hearing and who underscores so much of what we say in our Keep Listening messaging: the importance of regular hearing tests, how tinnitus can be a sign of hearing loss, how to properly use foam earplugs (roll and then insert), and how nothing smaller than your elbow should go in your ear.

The podcast created some cartoon graphics to help illustrate these “life kit” tips.

The New Yorker: Music critic Alex Ross asks, “What is noise?” He points out, as we have done and are mindful of, that one person’s noise is another person’s music. “Music is our name for the noise that we like,” he says, and it’s the premise for his review of noise/music.

He shows how we reject sounds we don’t like. For linguists, “The word ‘barbarian’ originates from a disparaging Greek term, bárbaros, which appears to evoke the alleged gibberish of foreign peoples (‘bar bar bar’).” Who knew!

Unfortunately Ross uses an older definition for noise, “unwanted sound.” Dan Fink has been working to get an updated definition in wider use—“noise is unwanted and/or harmful sound”—to acknowledge the deleterious effects noise can have not only on our ears but also our overall health.

Ross does talk about the confusion around the logarithmic scale (here following the New Yorker’s style of writing out all numbers): “A twenty-decibel sound is generally perceived as being twice as loud as a ten-decibel one, yet the actual intensity is ten times greater.” And per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “The risk of damaging your hearing from noise increases with the sound intensity, not the loudness of the sound.” (Italics mine.)

So while we may not hear a sound, whether it’s noise or music, as “just” twice as loud, the intensity is actually 10-fold—and that’s bad for our hearing. As Dan likes to say, if it sounds too loud, it IS too loud—to which we’d add: But we can listen and enjoy, responsibly.

We are so glad to see all this mainstream media coverage—it’s music to our ears!

*As an aside, as a lapsed journalist I am a little fascinated by the four different headlines given to the Scientific American story: “A Healthy Dose of Quiet” in the May 2024 print magazine; online as “Quiet! Our Loud World Is Making Us Sick” with a persistent sub-headline of “Turning Down the Noise Around You Improves Health in Many Ways”; and while the URL reads: everyday-noises-can-hurt-hearts-not-just-ears-and-the-ability-to-learn (a mouthful even for search engine optimization!).

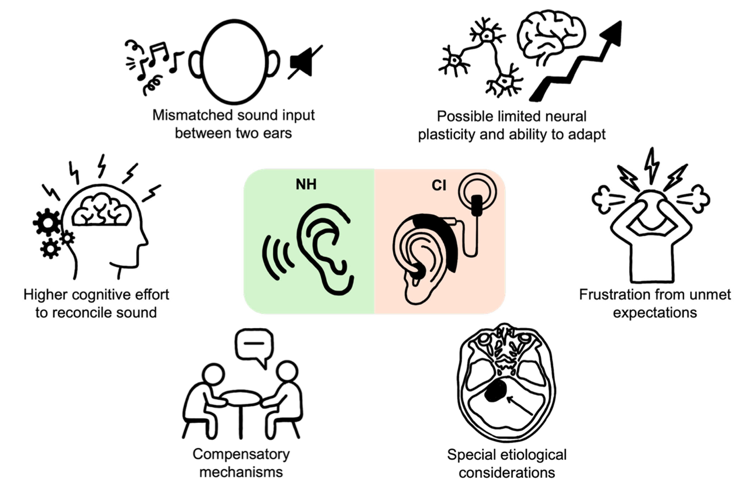

My area of study is auditory neuroscience, and I’m especially passionate about how neuroscience can reveal the underlying mechanisms behind why hearing outcomes vary so much from person to person.